Maybe, maybe not. The NYT headline blares “Tariffs Shrank Trade Deficit in September, New Data Show”. Imports did decrease from earlier, but that’s after a tremendous surge. The actual article is a more nuanced (i.e., that’s a lousy title).

Brad Setser, a trade expert at the Council on Foreign Relations, said the data showed “unambiguous weakness” in U.S. imports in September. “The question is how you want to interpret that,” he added. “Is this payback from the front running? Or are tariffs starting to have an impact?”

Mr. Setser said that it was too early to answer that question, but that global trade data suggested that U.S. imports could rise again in the next few months, fueled partly by the purchase of foreign computers and chips to build data centers.

I’m going to go with the “payback” thesis, combined with slowing economic activity. First consider the data; it’s not your typical time series import series.

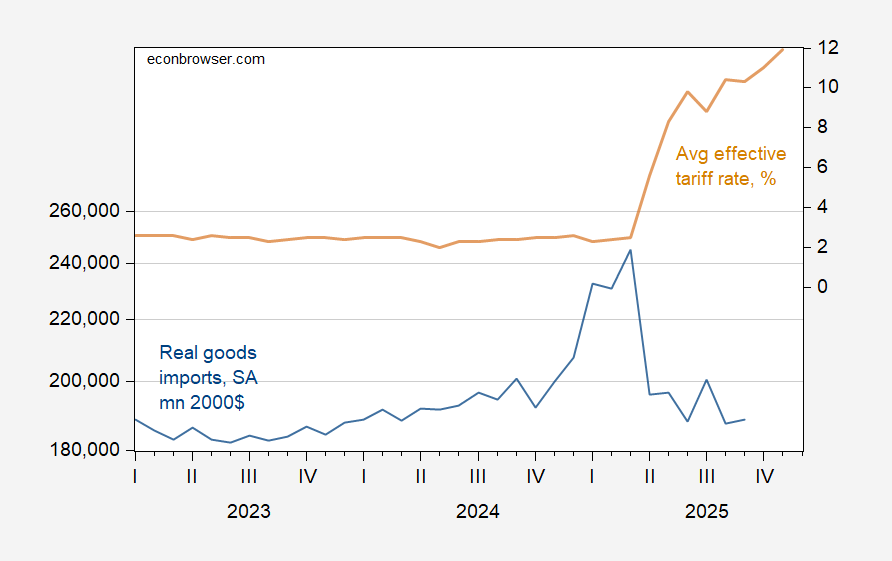

Figure 1: Real imports of goods, seasonally adjusted, in mn.2000$, BoP standard (blue, left log scale), and average effective tariff rate, % (tan, right scale). Source: Census, BLS via FRED, Paweł Skrzypczyńskiand author’s calculations.

Imports surged as importers tried to front-run the tariffs, and build up inventory. There’s an obvious surge going from November to March. How big? Quantitatively, pretty large; using a deterministic trend estimated over 2022M11-2024M10, I find the “excess imports” were about 133bn 2000$. Assuming front-running was to account for a year’s worth of imports, then I generate a counterfactual series.

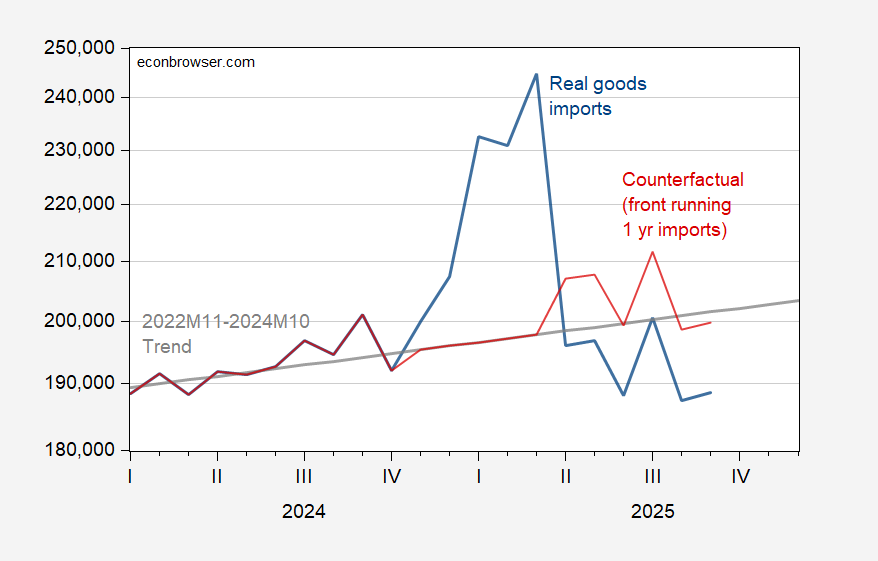

Figure 2: Real imports of goods, seasonally adjusted, (blue, log scale), 2022M11-2024M10 deterministic trend (tan), and counterfactual assuming one year’s worth of imports front-run (red), all in mn.2000$, BoP basis. Source: Census, BLS via FRED, and author’s calculations.

Viewed through this lens, imports have not decreased relative to what we would have otherwise seen. Of course, one year’s worth of import front-running is arbitrary; six months would imply imports are actually running higher than present.

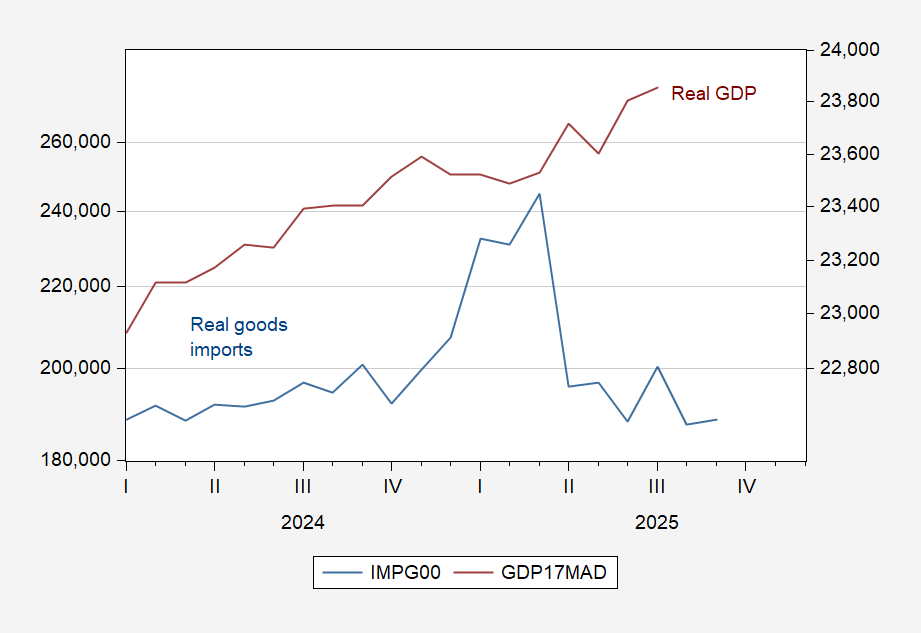

Imports depend on the real exchange rate and income as well as tariff rates. While the real value of the dollar has been pretty constant over the three months before September, income has apparently slowed, relative to pre-Trump. Since imports are highly income sensitive (I estimate 2.2 at quarterly frequency), it would not be surprising to see imports fall because of reduced economic activity, rather than expenditure switching arising from tariffs.

Figure 3: Real imports of goods, seasonally adjusted, mn.2000$ (blue, log scale), GDP in bn.Ch.2017$ SAAR (brown, right log scale). Source: Census, BLS via FRED, SPGMI 9/2 release, and author’s calculations.